A Constrcution of the Ministry of Finance on the ruins of the Qajar Palace, Tehran. Photo by Ali Khadem 1937. (Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies). graduation project for the second-year program of The Berlage, led by Amir Djalali, Francesco Marullo, Hamed Khosravi, and hosted by Technische Universiteit Delft, November 2012 – June 2013.

Constrcution of the Ministry of Finance on the ruins of the Qajar Palace, Tehran. Photo by Ali Khadem 1937. (Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies). graduation project for the second-year program of The Berlage, led by Amir Djalali, Francesco Marullo, Hamed Khosravi, and hosted by Technische Universiteit Delft, November 2012 – June 2013.

Housing Contemporary Forms of Life. A Project for Tehran

When life itself is put at work, any distinction between working and dwelling, production and reproduction, public and private, cease to exist. Contemporary capital parasites and makes productive any forms of life far beyond the body and the spatial-temporal coordinates of its movement, subsuming the whole complexity of relations, affects, desires as crucial driving forces of development.

The most typical domestic activities, traditionally concealed as “unproductive” and “servile” unpaid labour, have become paradigmatic forms of exploitation, to the extent that household management, reproduction, affectivity and care have become, today, the fundamental qualities of the ubiquitous field of labour precarity. In this sense, dwelling itself has been stripped out of its spatial organizations and traditional protective clichés, becoming the most profitable living performance of value production, triggering a progressive hybridization of the domestic space through a parallel and opposite feminization of labour and an internal masculinization of the Existenzminimum.

The emergence of such forms of life have progressively eroded the strict division between public and private space, blurring Hannah Arendt’s distinction between production, reproduction and political action. The city becomes at the same time a continuous field of exteriorised publicity and a sequence of autonomous, privatized interiors.

Tehran is a paradigmatic case of this phenomenon, in which collective life proliferates almost entirely in interiors. Commercial, productive and living activities are confined between the same architectural types which stretch throughout the metropolis as a continuous field of urbanization. In particular, the house is the place where all the economic, political, social, theological and class conflicts are deployed. Instead of being a “space of appearance,” the political space of Tehran is rather a walled space of concealment.

This form of organization is not entirely new in the Islamic city. Its archetype is the Medina, an inhabitable wall enclosing an internal space conceived as a ‘Terrestrial Paradise.’ As state in a state, a city in a city, the enclosure is a “micro-cosmos” recapitulating the collective organization of the political body. Thus, the Iranian house embodies many meaning: it is a theological category as well as the foundation of the Islamic state; at the same time it is the engine of production and the theatre of everyday resistance. Michel Foucault, in his famous articles from Tehran during the 1978 revolt, was fascinated by the political power of this duality, which he saw as the original contribution of Shi’ism: the possibility of “a religion that gave to its people infinite resources to resist state power.” Our project will see the dwelling as the theatre and the factory for this ever-present political constituency.

*

Tehran is a booming metropolitan area. Photo Hamed Masoumi 2008.

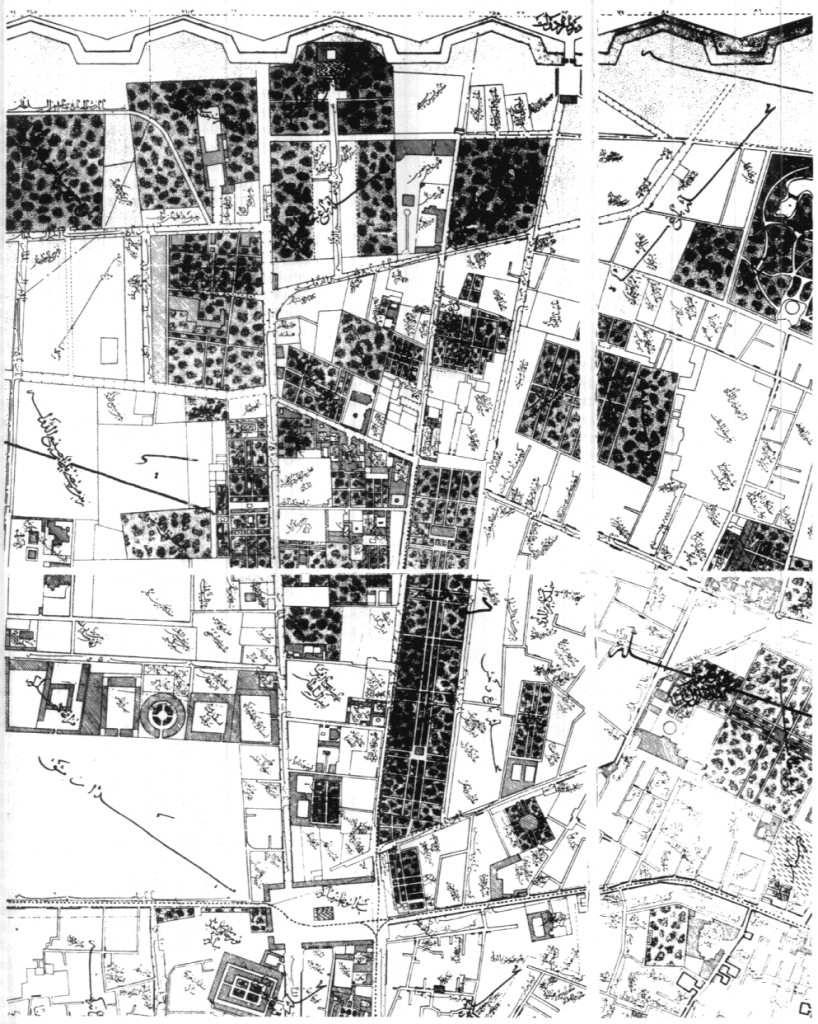

Photo Hamed Masoumi 2008. Detail of the 1889 Map of Tehran, by Abdol Ghaffar.

Detail of the 1889 Map of Tehran, by Abdol Ghaffar. Meydan-e Toupkhaneh, Tehran 1890. Photo Antoin Sevruguin. (Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives) Due to the development of an extensive network of infrastructure it is constantly being densified and expanded in its periphery, shaping a linear stretch of urbanisation enclosed between the Alborz mountain range in the north and the desert in the south. The historic centre has so far lacked political attention. Suffering from pollution, inaccessibility, lack of open spaces and ageing, the centre has gradually been abandoned by its inhabitants. The historic centre which used to be the heart of social, political and commercial life of the city now has turned to a congested traffic node punctuated with the traces of the recent past such the Golestan palace, the Friday mosque, and the bazaar, which is progressively losing importance in the new economy of the city.

Meydan-e Toupkhaneh, Tehran 1890. Photo Antoin Sevruguin. (Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives) Due to the development of an extensive network of infrastructure it is constantly being densified and expanded in its periphery, shaping a linear stretch of urbanisation enclosed between the Alborz mountain range in the north and the desert in the south. The historic centre has so far lacked political attention. Suffering from pollution, inaccessibility, lack of open spaces and ageing, the centre has gradually been abandoned by its inhabitants. The historic centre which used to be the heart of social, political and commercial life of the city now has turned to a congested traffic node punctuated with the traces of the recent past such the Golestan palace, the Friday mosque, and the bazaar, which is progressively losing importance in the new economy of the city.

The centre still bears the traces of the old city of Tehran enclosed within an octagonal wall built in 1879. Fascinated by European city shapes, in order to make the ‘new city’ as his own capital, Shah Naser ed-Din ordered the demolition of the old 1554 city wall and the anachronistic construction of a bastioned wall in the French manner.

The old Tehran city fabric had been shaped based on the traditional Islamic city configuration: placement of the Great Mosque, the Palace and Bazaar around an empty core, the meydan. The project of modernization of the capital run by the king in the mid-19th century needed a fundamental re-conceptualisation of the city, in the attempt to secularize its spaces. Accordingly, the shah ordered the construction of a new meydan—the Toopkhaneh—no longer surrounded by religious institutions, but by secular equipments: banks, the municipality, the post office and the police headquarter.

The square, which in the meantime had become the epicentre of political action and public demonstrations, was demolished in the mid-60s and never reconstructed again. The centre started progressively to lose architectural definition, hosting all kinds of urban functions in relatively small inhabitable cells, while the residential units gradually became emptied and abandoned. Today, due to the resettlement of the bureaucratic and administrative centre of the city into a new location a few kilometres northwards of the city centre, rethinking the very recent future of the historic centre seems be urgent. Several architectural offices were commissioned by the municipality of Tehran to revitalise the historic centre as a habitable space. The studio will take this occasion to tackle the very problem of the city through a fundamental rethinking of new housing typologies supported by a strategic plan, and reinforced by the infrastructural development.

*

The work produced by this studio aims to tackle the production of the city through its architecture, taking the dwelling as a political form that embodies social, historical and political issues. Through a rigorous historical account of the political and social development of the forms of dwelling in Tehran and in the Islamic city in general, the studio aims to relate with the municipality plans for the regeneration of the historical centre of Tehran, addressing also specific problems of real estate, infrastructural equipment and transportation.

Exercises in redrawing and reconstruction will constitute the first phase of the studio. Reconstruction is a fundamental strategy through which architecture expresses itself politically. Against reconstruction as a restoration of monuments into an idealized “original” condition, as a mere recuperation of ready-made past mythologies for an ideological present use, reconstruction will be seen as a critical operation which does not efface the historical complexity but, on the contrary, takes it as its main element for the elaboration of a new project for the city.

A particular importance will be given to reading and writing. The production of theory is a central component of the architect’s job. Theory might not be necessarily explicitly reflect the outcome of design. Nevertheless, the understanding of reality through theoretical discourse is a prerequisite to construct critical thought for further architectural praxis. Thereby the participants are encouraged to search in the work of philosophers, political economists and artists not only for the content to found their own discourse, but to look for new forms of reflecting upon the architecture of the city.