First published in Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 38:1 (2014), 39-53.

[1] In the Islamic text paradise (al-firdaws) is differentiated from the gardens of heaven while they frequently appear in the whole Quran text as Jannah (literally means garden). It has been quoted from Prophet Muhammad in Dur al-Manthur “Heaven has hundred levels and among these ranks between the earth and the sky, Paradise is the most prosperous place.” In Quran Paradise occurs two times in the whole text. The first is in Al-Kahf “Lo! Those who believe and do good works, theirs are the Gardens of Paradise for welcome” (18: 107). And in the Al-Mumenoon “And who are keepers of their pledge and their covenant, and who pay heed to their prayers. These are the heirs, who will inherit paradise. There they will abide” (23: 8–11).

[2]“These are the limits [set by] Allah, and whoever obeys Allah and His Messenger will be admitted by Him to gardens [in Paradise] under which rivers flow, abiding eternally therein; and that is the great attainment.” (4: 13); “Allah has promised to the believers -men and women, – Gardens under which rivers flow to dwell therein forever, and beautiful mansions in Gardens of Eden. But the greatest bliss is the Good Pleasure of Allah. That is the supreme success.” (9: 72).

[3] See Bremmer, J. N. 1999. Paradise: from Persia, via Greece, into the Septuagint, in G. P. Luttikhuizen (Ed.). Paradise interpreted: representations of biblical paradise in Judaism and Christianity. Leiden: Brill.

[4] Driscoll, J. F. 1912. Terrestrial paradise, in The Catholic encyclopedia, vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 519 p.

[5] Harper, W. R.; Wallace, J. 1893. Xenophon’s Anabasis, seven books. New York: American Book Company. 92 p.

[6] The term Paradise occurs only three times in the New Testament: First in Luke 23: 43, “And Jesus said to him: Amen I say to you: This day you shall be with me in paradise.” The second one is in the second Corinthians, St. Paul describing one of his ecstasies tells his readers that he was “caught up into paradise” and the third appearance is in the Apocalypse 2: 7, where St. John, receiving in vision a Divine message for the “angel of the church of Ephesus”, hears these words: “To him that overcometh, I will give to eat of the tree of life, which is in the paradise of my God.” The first two are explicitly associated with the concept of heaven and they apparently replaced the term, however the third occurrence signifies the image of the ‘Garden of Eden’ as it appears in the Book of Genesis.

[7] See Harper, W. R.; Wallace, J. 1893. Xenophon’s Anabasis, seven books. New York: American Book Company; Gorham, G. M. 1856. The Cyropaedia of Xenophon. London: Whittaker; Prickard, A. O. 1907. The Persae of Aeschylus. London: Macmillan and Co.

[8] The Islamic way of life is defined based on two main sources of Islamic laws (orders) and the life of the Prophet and his representatives and true companions (rules).[9] For more information on the Early Islamic Cities and the idea of medina, see www.thecityasaproject.org/2012/06/medina/

[10]The community of faithful (ummah), as it is described in the Quran, is the Islamic society that lives under an Islamic state, whom their only unifying principle is the faith in the Islamic ideology and its political manifestation. This concept is a divine commandment and a definite mission assigned by God, who commands Muslims to be a social totality, the ummah. Since the very beginning of the formation of the Islamic state, in a very political move, the concept of ummah was delegated to abandon the relationship to the land, which is in the idea of nation. It appears in Quran (21: 92) when God addresses the community of faithful. “Verily, [O you who believe in Me] this community of yours is one single community, since I am the Sustainer of you all: worship, then, Me [alone]!”

[11] The first Islamic cities were built in the Mesopotamia, which was part of the Sassanid Empire at that time, and not in Arabian Peninsula.

[12] Hanaway, Jr. W. L. 1976. Paradise on Earth: the terrestrial paradise in Persian literature, in E. B. Macdougall, R. Ettinghausen (Eds.). The Islamic garden. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University. 63 p. Fig. 1. Iranian Bāgh (garden). The burial place of Omar Khayyam at Nishapur. Source: Mousavi, A; Stronach, D. 2012. Ancient Iran from the Air. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

Fig. 1. Iranian Bāgh (garden). The burial place of Omar Khayyam at Nishapur. Source: Mousavi, A; Stronach, D. 2012. Ancient Iran from the Air. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

[13] Pinder-Wilson, R. 1976. The Persian garden: Bagh and chahar bagh, in E. B. Macdougall; R. Ettinghausen (Eds.). The Islamic garden. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University. 70–85. Fig. 2. Perisan Garden, Chaharbāgh, Fars- Iran. Source: Gerster, G. 2008. Paradise Lost: Persia from Above. London: Phaidon.

Fig. 2. Perisan Garden, Chaharbāgh, Fars- Iran. Source: Gerster, G. 2008. Paradise Lost: Persia from Above. London: Phaidon.

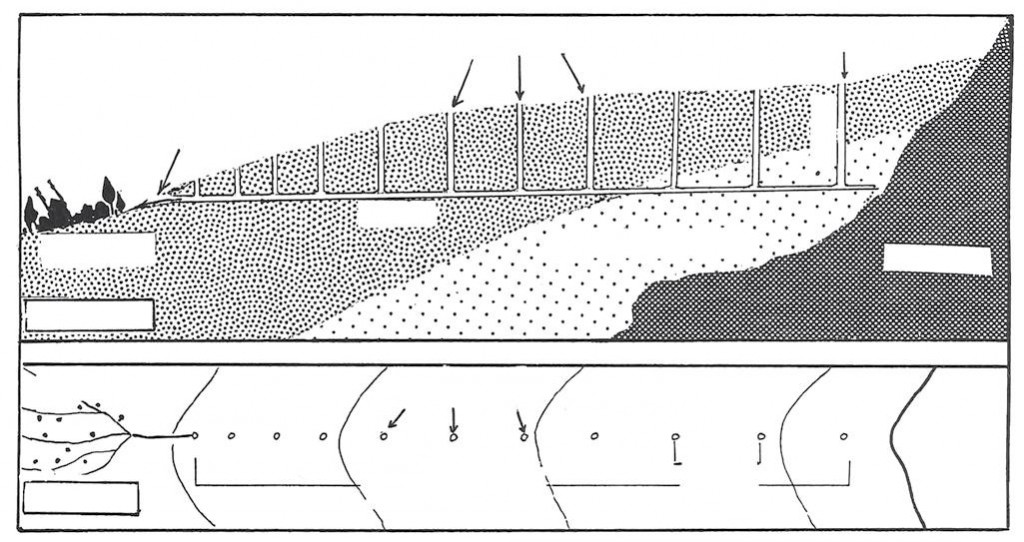

[14] Smith, H. H. 1971. Area handbook for Iran. Washington, DC: American University. Fig. 3.Qanat structure, schematic section. Source: Kheirabadi, M. 2000. Iranian Cities: Formation and Development. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Fig. 3.Qanat structure, schematic section. Source: Kheirabadi, M. 2000. Iranian Cities: Formation and Development. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

[15] Kheirabadi, M. 2000. Iranian cities: formation and development. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. 93 p.

[16] The Achaemenids had a keen interest in horticulture and agriculture. Their administration greatly encouraged the efforts of the satrapies toward innovative practices in agronomy, arboriculture, and irrigation. Numerous varieties of plants were introduced throughout the empire. See Morris, C. D. 1880. Xenophon’s Oeconomicus, The American Journal of Philology

[17] Stronach, D. 1990. The garden as a political statement: some case studies from the Near East in the First Millenium B. C., Bulletin of the Asia Institute (4): 171–80.

[18] For more information on Pasargadae see Stronach, D. 1989. The royal garden at Pasargadae: evolution and legacy, in L. De Meyer, E. Haerinck, (Eds.). Archaeologica iranica et orientalis: miscellanea in honorem Louis Vanden Berghe. Ghent: Peeters Presse 476–502. Fig. 4. The plan of the Royal City of Pasargadae. Source: Reproduced by the author after Stronach.

Fig. 4. The plan of the Royal City of Pasargadae. Source: Reproduced by the author after Stronach.

[19] Lincoln, B. 2007. Religion, empire and torture: the case of Archaemenian Persia with a postscript on Abu Ghraib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 57 p.

[20] Happiness of mankind appears as šiyãti martyahyã in the Old Persian. The word šiyãti (happiness) appears in Modern Persian as šãdi. It is the divine power (the sovereign state, the emperor), which should re-establish this happiness throughout the empire by literally constructing the perfect model. According to Achaemenid inscriptions, it is the King’s (the emperor’s) duty to restore the lost happiness of mankind. It has been written in Darius’s tomb (Naqš-i-Rostam): “The great God is Ahura Mazda; who created the earth; who created the sky; who created mankind; who established happiness for mankind; who made Darius the king…” see Lincoln, B. 2003. À la recherche du paradis perdu, History of Religions 43(2003): 139–154.

[21] ibid.

[22] Avesta (Zoroastrian Holy Book), Fargard 3, section 18.

[23] Hana means, literally, ‘an old man’; Zaurura, ‘a man broken down by age’; Pairishta-khshudra, ‘one whose seed is dried up’. These words have acquired the technical meanings of ‘fifty, sixty, and seventy years old’.

[24] Healy, P. 2007. La Difesa della Natura, notes for the exhibition organised by F.I.U Amsterdam in 52nd Venice Biennale.

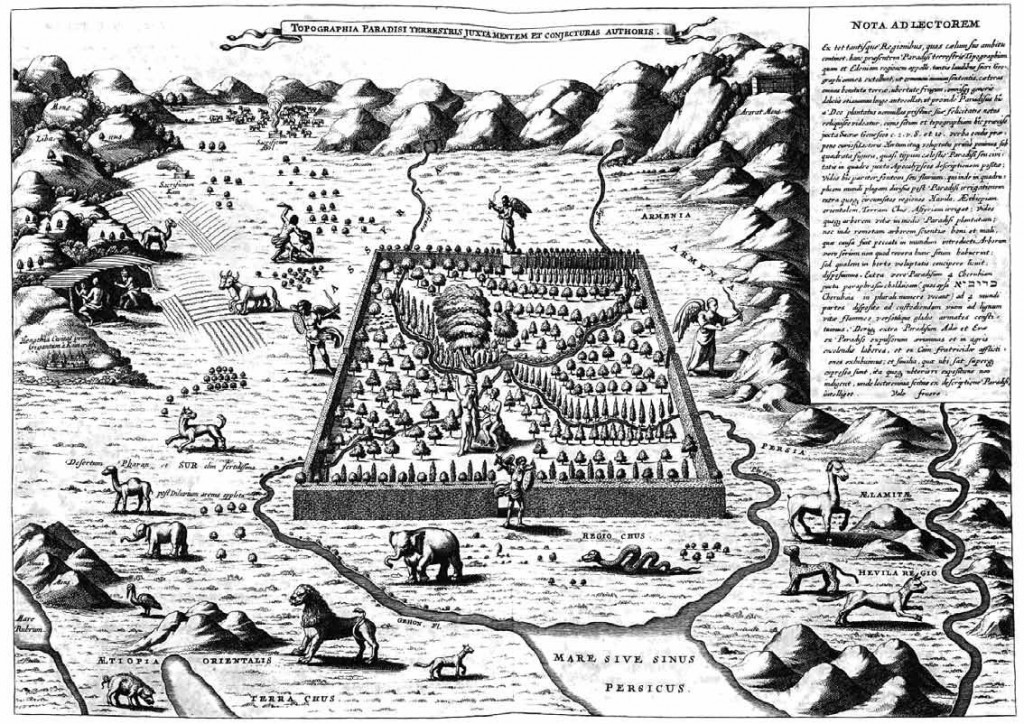

[25] Kircher, A. 1675. Arca Noë. Amsterdam: J. Janssonium a Waesberge. 230 p. Fig. 5. Terrestrial Paradise. Source: Kircher, A. 1675. Arca Noë. Amsterdam: J. Janssonium a Waesberge.

Fig. 5. Terrestrial Paradise. Source: Kircher, A. 1675. Arca Noë. Amsterdam: J. Janssonium a Waesberge.

[26] Lincoln, B. ibid.

[27] See the original Arabic text in al-Tabari, M. 2007. Annales or Tarikh al-Tabari, vol. 9. Damscus-Beirut: Dar ibn Katheer. 932 p.; The English translation is taken from Beckwith, C. I. 1984. The plan of the city of peace, Acta Orientalia Hungarica 38(1984): 143–164.

[28] The name of Baghdad is presumably a compound Persian word; Bagh means God and Dad denotes the act of founding. Baghdad then would have signified the city ‘Founded by God’ or the ‘City of God’.

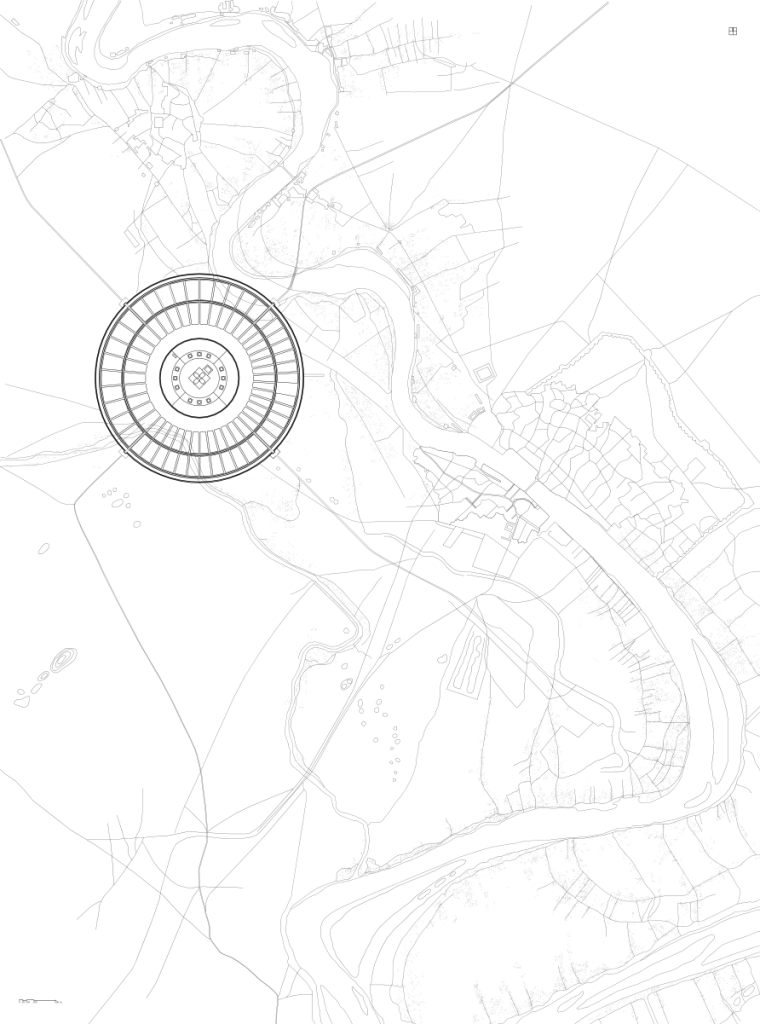

[29] ‘This day was chosen by Nowbakht because, at that moment Jupiter (the most fortunate planet) was presided over the birth of Baghdad.’ Wendell, C. 1971. Baghdad: imago mundi, International Journal of Middle East Studies 2(1971): 99–128. Fig. 6. The City of Peace (Baghdad during al-Mansur) and its surroundings. Source: Reproduced by the author after Herzfeld.

Fig. 6. The City of Peace (Baghdad during al-Mansur) and its surroundings. Source: Reproduced by the author after Herzfeld.

[30] He was actively involved in advising the ruler’s construction projects, apparently designing some unusual siege machines during his campaigns and governorship in Tabaristan, and also building a palace for himself at Amul, the capital. He was fully aware of the circular Sassanid cities, especially Gur and Darabgird, Beckwith, ibid.

[31] A general assumption out of various accounts that described the foundation of the City of al-Mansur, indicates that Khalid was responsible for the planning of the city, however he was accompanied by a group of architects who were developing design and construction of the buildings. Four frequently mentioned figures are Abd Allad ibn Muhriz, Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, Imran ibn al-Waddah and Shihab ibn Khathir.

[32] Many scholars, such as Creswell, have suggested that the circular plan of the Sassanid cities of Gur (firouzabad) and Darabgird influenced the plan of Baghdad during al-Mansur.

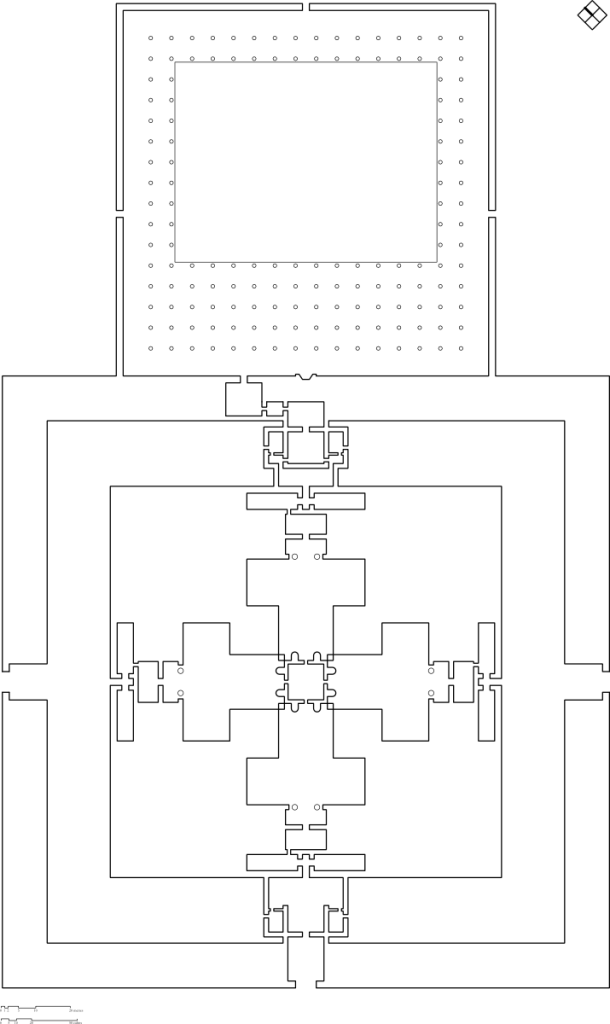

[33] According to Creswell, the most reliable dimensions of the city is given by Herzfeld, who following al-Yaqubi’s description, suggests a circumference of 20,000 cubits for the Round City. Therefore the diameter of the circle must have been around 6368 cubits or 3300 metres, see Creswell, K. A. C. 1940. Early Muslim architecture, part II. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 7–8. Fig. 7. Hypothetical Plan of the Great Mosque and the Palace of Green Dome. Source: Reproduced by the author after Creswell.

Fig. 7. Hypothetical Plan of the Great Mosque and the Palace of Green Dome. Source: Reproduced by the author after Creswell.

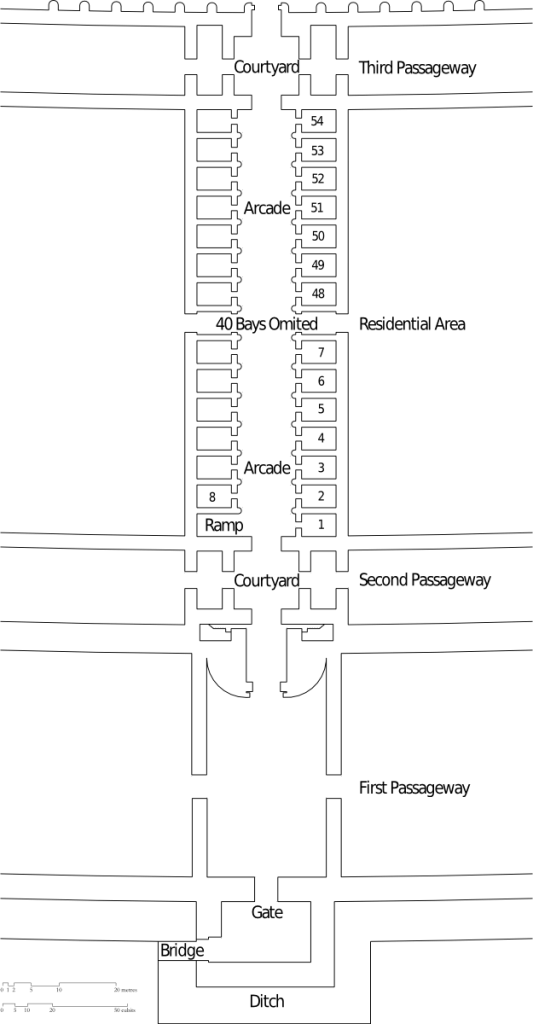

[34] Wasit was one of the first Islamic cities, founded by Al-Hajjaj in Mesopotamia. See Creswell, K. A. C. 1979. Early Muslim architecture, vol. I, part I. New York: Hacker Art Books, 132. Fig. 8. Hypothetical Plan of the Main Road, the City of Peace. Source: Reproduced by the author after Creswell.

Fig. 8. Hypothetical Plan of the Main Road, the City of Peace. Source: Reproduced by the author after Creswell.

[35] Le Strange, G. 1900. Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. 33–34.

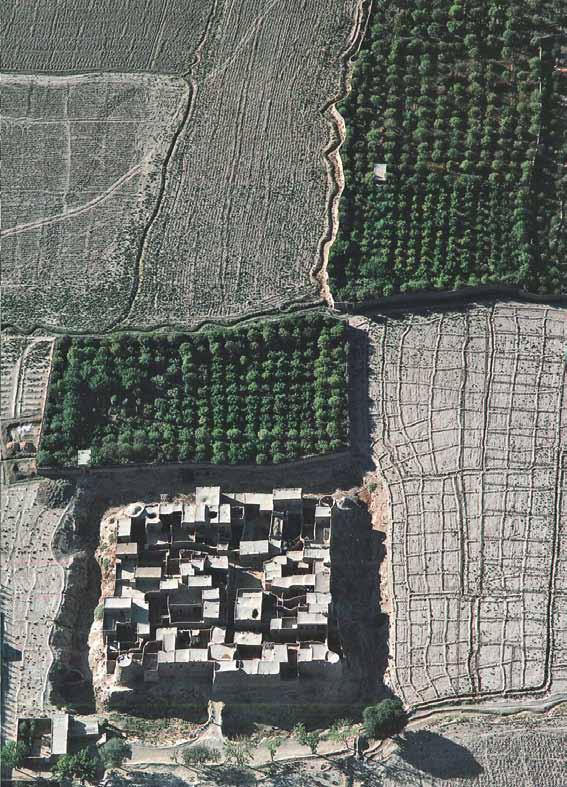

[36] Unlike other city-camps of early Islamic period, which were mostly occupied by the Arab tribes who were transplanted from the main Arabian land, in Baghdad the inhabitants chose to live there voluntarily. Fig. 9. Garden as the Index of the City. A village near Neyriz. Source: A. Mousavi, D. Stronach, Ancient Iran from the Air (Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2012)

Fig. 9. Garden as the Index of the City. A village near Neyriz. Source: A. Mousavi, D. Stronach, Ancient Iran from the Air (Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2012)

[37] Le Strange, ibid.

[38] al-Yaqubi, A. 1861. Kitab ol-boldan or Book of the countries. Leiden: Brill, 11–13.

[39] A distinctive point about Baghdad, in comparison to the other cities of the time, was the presence of police instead of the army. The police was tasked to take care of the organisation of the city as well as the citizens, not as a militant force but more as a governing body.

[40] In the quadrant of houses on the south side, that between the thoroughfares leading respectively to the Basra and Kufa Gates, the Caliph built his great prison called Matbak, standing in the street of the same name, ‘constructing it with well-built walls and solid foundations;’ and until the reign of Mutawakkil, grandson of Harun al-Rashid. This remained the chief prison of Western Baghdad.

[41] The cause of the removal of the markets from the arcades is thus related by al-Tabari (and has been copied by many other authorities): The Emperor of the Greeks had sent one of his Patricians on an embassy to al-Mansur, and before the envoy was dismissed back to Constantinople, the Caliph ordered his chamberlain Rabi to conduct the Greek over his new capital, namely the Round City, then recently completed. So the envoy was shown over all the new buildings and palaces, and was taken up on the tops of the walls and into the domes above the gateways. At the farewell audience, the Caliph inquired what the Greek had thought of the new city, and he received these words in reply: ‘Verily (said the envoy), I have seen handsome buildings, but I have also seen that thy enemies, O Caliph, are with thee within thy city.’ For explanation he added that the markets within the city walls, being always full of foreign merchants, would become a source of danger, since these foreigners would not only act as spies for carrying information to the enemy, but also being domiciled in the markets, they would have it in their power traitorously to open the city gates at night to their friends outside. Pondering over this answer, the Caliph al-Mansur– as the chronicle says– ordered the markets to be removed to form suburbs outside the various gates, Le Strange, ibid.

[42] The first siege of Baghdad between the troops of al-Amin and al-Ma’mun, who fought for taking the throne after their father’s death, the walls of the city were demolished. Except some buildings like the Prison and the Great Mosque, most parts of the buildings were abandoned and the city of Baghdad started grow mainly on the East bank of Tigris with new palaces, mosques and institutional buildings. However the life of Abbasid Baghdad came to a dramatic end in 1285 A.D. by the Mongols’ invasion.

[43] However at the beginning of the 20th century, due to archaeological explorations, historians and archaeologists confirmed some of the spatial features of the City of Peace, it was mainly through the text that the city has been portrayed. In fact like any other ideal city, the City of Peace, has emerged from the literary accounts. In the way it lived the distinction between the reality and the imaginary disappears and it became an ideal model which even inspired philosophers and thinkers; indeed it was not by chance that al-Farabi completed his most celebrated manifesto on the ‘excellent city’ during his life in Baghdad.

Fig. 10. Inhabitable Walls. Aerial Photo of a Small City in Khorasan, Iran. Source: Paradise Lost: Persia from Above (London: Phaidon, 2008).

[44] Schmitt, C. 2005. Political theology: four chapters on the concept of sovereignty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 5 p.

[45] al-Farabi, M. 1985. The perfect state or Mabadi ara ahl al-madina al-fadila. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.[46] ‘For the relation of the First Cause (God) to the other existents is like the relation of the king of the excellent city to its other parts’, al-Farabi, ibid.

[47] ibid.

[48] Stewart, S. 1966. The enclosed garden. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. 59 p.

[49] Matteucci, P. 2006. Sovereignty, border, exception, in P. Bonifazio, E. Bellina (Eds.). State of exception. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press. 14 p.

[50] Agamben, G. 2005. State of exception. Chicago: Chicago University Press. 70 p.

[51] ‘When life and politics -s originally divided, and linked together by means of the state of exception that is inhabited by bare life – begin to become one, all life becomes sacred and all politics becomes the exception,’ Agamben, G. 1998. Homo sacer: sovereign power and bare life. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 86 p.

[52] ‘A life that cannot be separated from its form is a life for which what is at stake in its way of living is living itself. What does this formulation mean? It defines a life –human life – in which the single ways, acts, and processes of living are never simply facts but always and above all possibilities of life, always and above all power (potenza),’ Agamben, G. 2000. Means without end: notes on politics. Minneapolis-London: University of Minnesota Press, 4–5.

[53] Cavalletti, A. 2005. La Città Biopolitica. Milan: Mondadori. 206 p.

[54] Agamben, ibid.

[55] In his book, The Highest Poverty, Agamben brings an example of the monastic life, where he argues that it is not only the divine rule, which designates the lives of the monks, but also it is precisely the way that these monks live which shapes the monastic rule. The monastery is a house (habitat) that accommodates a particular form of life and, and also it is the way of living (habitatio), Agamben, G. 2013. The highest poverty: monastic rules and form-of-life. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 13–16.

The early Islamic cities embodied a new way of living, promoted and supported by the Islamic law and the life of the Prophet and his successors. The idea of ‘paradise’ as a reward for the Muslim faithful was the basic concept developed by Muhammad from the beginning of his apostolic mission in Mecca. [1] This was more than an abstract vision of future bliss because the Prophet made many specific statements as to the garden’s iconography, topography, its nature and its inhabitants. Since then these descriptions have played an important role in the Muslim ideology in relation to the built environment.

The Quranic descriptions of the celestial gardens are consistent to convey an impression of greenery, overflowing fountains, rivers, foods and sensual beauty to be found in that place. They are illustrated as ‘enclosed’ spaced that you have to enter, where you shall ‘dwell in’. [2] This image, apparently, follows the description of the Garden of Eden in the Book of Genesis. Originally, it is in the Greek translation of the Old Testament, the Septuagint, in which for the first time the idea of paradise coincided with the image of garden. [3] James F. Driscoll in The Catholic Encyclopaedia, under the term ‘Terrestrial Paradise’, writes: The association of the term [Paradise] with the abode of our first parents does not occur in the Old Testament Hebrew. It originated in the fact that the word paradeisos was adopted, though not exclusively, by the translators of the Septuagint to render the Hebrew [term] for the Garden of Eden described in the second chapter of Genesis. It is likewise used in diverse other passages of the Septuagint where the Hebrew generally has ‘garden’, especially if the idea of wondrous beauty is to be conveyed. [4]

One of these images of paradise comes in the Song of Solomon, roughly contemporary with Xenophon, which describes a royal garden in fabulously sensual language and images: ‘a large and beautiful paradeisos, possessing all things that grow in the various seasons’ or ‘a large and beautiful paradeisos, shaggy with all kinds of trees’. [5] These descriptions not only depicts the Judeo-Christian image of the celestial Garden but rather matches the actual spatial configuration of the Iranian gardens to be found in the Iranian Plateau long before the advent of Islam. [6] The celestial garden is described mostly with topographic features where the water flows on the valleys (underneath the planted region). There are detailed descriptions of four rivers, which come together in the gardens, which remind us the cruciform water-channels of the typical Persian gardens. In fact, it was by the Greek authors, which the image of Persian (or in that time Achaemenid) garden represented as an exotic planted oasis. [7] However due to the hostile landscape of the Persian territory, the garden was an exceptional built environment. Various trees, animals and irrigation system were parts of the microcosmic model of the imperial economy, where all manner of goods and resources flowed from the provinces to the centre.

Moreover the Quranic verses (following the Judeo-Christian texts) illustrate the celestial garden as a ‘permanent house’ and not only a place for everlasting pleasure. Architecturally this depiction seems not referring to what was the form of living in the Arabian Peninsula at the rise of Islam, while it matches more the reality of the ‘earthly gardens’ of Sassanid Iran. In development of the Islamic ideology, the Terrestrial Paradise got same attention and importance as the celestial garden; indeed these two realms address two different, yet connected aspects of life which had to be formed and controlled carefully by following certain way of living. [8] This would ultimately lead humankind towards achieving a life fulfilled with felicity and happiness.

Quite contrary to the common form of tribal settlements in Arabia, Islam promoted ‘urban life’ as the essential path to accomplish the ideal life. Consequently medina became widely practiced model, to provide a frame to support, and at the same time to control a specific way of living in the new empire. [9] Through its spatial organization, medina mirrored the celestial garden (garden of Eden) on earth; the Muslim rulers aimed to reconstruct the original house of mankind not only to resemble the heavenly state of peace but also create a minimum structure that could protect life and enable it to reach to its final goal. This spatial condition therefore was reduced to a diagram that embodied three necessary relationships: the link between the believers (ummah), [10] between the individuals and the Islamic ruler (the Prophet or his successors), and ultimately between the community of faithful and the territory.

Bāgh, spaces of re-creation

The analogy between the early Islamic cities and garden did not appear only in the metaphorical aspects but in fact these terrestrial gardens, followed the physical configuration of the garden-cities already existed in pre-Islamic times, commonly called bagh(in Persian) or garden. These urban artefacts were inevitable form of built environment in the arid topography of the larger Iranian plateau. [11] Gardens in Persian territory are always behind a wall. On the outside is the desert, representing desiccation and death, the harsh reality of life on the Iranian landscape. Within the wall are flowers, fruit, shade, water and life. While there are real and tangible, the contrast with what is outside the wall is so striking as to make the interior a veritable paradise on earth.[12] However the form of these gardens was intimately related to its function, as a mechanism that could makes certain form of life flourish within the hostile environment. (Fig. 1) In fact the etymology of the term can help revealing its manifold meaning. Bagh originally is derived from the Indo-European root bhag that means ‘to share out’, ‘to enjoy’. It comes in the Old Persian and Avestan as baga that means ‘distributor of good fortune’. In its Modern Persian usage, the term appears in two forms of bagh (short –a- sound) as ‘God’, and bāgh (long –a- sound) as ‘Garden’. Interestingly while these terms seem to connote two radically different meanings, they address the same concept, which is the act is the ‘distribution’ and ‘allocation’ of life. More than being a space for leisure or agriculture, Iranian gardens were the only spatial configuration wherein any form of life was possible; they were in fact life-sustaining camps in the literal tabula rasa of the Iranian plateau.

Chaharbagh

The typical spatial configuration of the Iranian gardens is knows as chaharbagh (literally four-garden). While the evidences of this typology are traceable since the sixth-century B.C., there are few accounts that give precise description of the architectural form and configuration of chaharbagh. In one of the surviving treaties, Irshad al-Zara’ah, Qasim ibn Yusef who composed it at Herat in 1515, conducted a detailed study on the ways of managing the land and planting. Among the four treaties two are on the mathematics and geometry (multiplication and division with reference to circles and other geometric figures) in their very practical application for the circulation of grain and for construction of tents and pavilions; the third is concerned with the distribution of well waters, manipulation of topography and the economy of the city of Herat. The Chapter 8 of Irshad al-Zara’ah, specifically addresses ‘The layout of the chaharbagh and its pavilion’. Chaharbagh is described as a rectangular walled platform, divided by paths or two waterways (a cross) into four symmetrical sections. It set on the ground, which rises to the north thus allowing for the water flow. Two streams, each a cubit in width are led round the garden; the first, three cubits from the wall, is separated from the second and inner stream by a path three cubits wide. The main canal flows down the centre of the garden into a pool, which is some twenty cubits from the pavilion. Just inside the wall there are rows of shade-giving trees – pine tree or cypress, which are restricted to the outer bank of the first stream. The fruit-bearing trees planted on a grid-pattern within the four plots, divided by the two main water axes, where the flowers planted in the same manner on the perimeter of the plots.[13] In fact as Qasim ibn Yusef composed his treaties, the garden, or specifically chaharbagh, was part of the series of engineering for the management of the territory and founding the cities. Indeed garden is an urban artefact through which the life is allocated (water supply), protected (wall) and managed (grid) on the land (Fig. 2).

The most shared feature of this territory is scarce and limited water resources. Regions with a mean annual rate of precipitation less than eight inches constitute the major portion of the territory. [14] Considering the fact that this amount of water is inadequate for dry agriculture, the existence of many cities in this plateau is fully dependent on availability of subsurface water reservoirs that have historically been used by the habitants of the land to make life possible within this harsh environment. The presence of subsurface water reservoirs is related to the geological history of the Iranian plateau. Heavy rains and violent floods of the glacial periods resulted in severe erosion of mountain rocks that were pulverized and transported to the foothills and nearby plains. Because these lands contain irregular layers of sand and pebbles, they form considerable water reservoirs. The particular surface configuration of the Iranian landscape and the available irrigational technology through qanats, allow this water to be moved to the lower lands to be used for drinking or irrigation (Fig. 3). Similar to foundation of cities, the construction of qanats always starts with some religious ceremony and many ritual preparations. [15] Most of the time these underground networks were constructed before building the actual physical structure of the cities and gardens. This process was operated through series of instrastructural interventions and territorial management in order to provide the necessary conditions for life. Indeed through various forms of rituals and performances the founders imitated the moment of re-creation.

In the Iranian landscape gardens were not only limited to the agricultural units or royal parks, but in fact, they were the minimum structures to make any form of life and human settlement possible. In this way the Persian garden was a diagram of city. While construction of these urban artefacts required precise knowledge of topography, ground layers and mechanics, it also presupposed the performance of a powerful executive authority that can run such a project in a territorial scale. These ‘garden-cities’ epitomize a unique urban form, which is, to a great extent, an ideological-historical response to the natural environment in which life constantly confronted with death and maintaining a life was an exceptional deed. The built environment therefore created micro-cosmos within the extreme landscape; camps that protected life and let it flourish within the tabula rasa. In such a condition any distinction between various forms of life ceases to exist and life becomes the ‘ideal life’, kings represent God and city becomes paradise.

Since the first millennium B.C., the garden has been an integral part of Persian architecture, be it imperial or vernacular. [16] By referring to the original meaning of bagh, it become clear that these gardens were not limited to the royal park, hunting grounds or agricultural fields, they were the most common form of the built environment through which the extreme geographical condition was tamed the life became possible. Regardless of the practical aspects of the garden and its sensual pleasures, these artefacts also incorporated political, philosophical, and religious symbolism. These camps, since the Achaemenid Empire, became the political institution through which a certain urban form was defined that spread throughout the empire. The idea of the king creating a fertile garden out of barren land, bringing symmetry and order out of chaos, and duplicating the ‘divine paradise on earth’, constituted a powerful statement symbolizing authority, fertility, and legitimacy. [17] This idea of the ‘king-gardener’ is well-recorded in case of Achaemenid king, Cyrus and his capital city Pasargadae. The royal city included a magnificent rectangular garden at the centre of the palace complex, alongside a portico with colonnade. Inside the portico was located a royal throne and a number of seats reserved for nobles, who were able to gaze out on the garden from this covered space or descend and stroll through the vegetation. The walls that enclosed the garden had two gates, which admitted visitors and water through two irrigation channels, connected to an extensive network of qanats. Inside, the space was divided into four sectors, representing the four cardinal directions. Indeed Pasargadae is one of first historical evidences of the use of typical Iranian Chaharbagh structure in construction of a city. [18] Except bagh, which indicates the general idea of garden, Achaemenids called their urban entities, pairi-daeza or paradise (Fig. 4).

Paradise

Zoroastrian texts characterise the universe as the opposition of two poles: the Wise Lord (Ahura Mazda) and the Evil Spirit (Ahriman). However this doctrine constitutes the Wise Lord and his original creations as entirely good, the world’s imperfections were understood to have appeared at a later moment, as the result of what is usually called ‘the Assault’ of the Evil Spirit. [19] In this conflict the very goal of mankind is to protect itself from the evil forces – represented in the three main categories of the lie, famine and the enemy. This protection can only happen through the dominating power of the sovereign, he who builds the most perfect earthly place: paradise, in order to have society attain the ultimate purpose of creation, which is happiness.

Therefore the idea of the city, for the Persians, was firmly bound to the ultimate goal of creation, which according to Zoroastrian ideology is ‘Happiness for mankind’. [20] It is the divine power (the sovereign or the emperor), which should re-establish this happiness throughout the empire by literally constructing the ideal model. This ‘ideal state of peace’, appears in the form of the walled estate, by preventing the main three evil forces: the enemy, the lie and famine. It is in a way the restoration of the ideal moment of creation. Therefore paradise is ‘a space of re-creation in the most precise and most profound sense’. [21] This ideological spatial model has been described in the surviving accounts emphasising its exquisite beauty, the abundance of water, and the profusion of plants and animals with which it was filled: that is, the elements which constitute the sustenance – and, more importantly – the happiness of mankind.

Indeed, the root of the word Paradise (pairi-daeza) nevertheless does not bear any idea of a holy secured garden, however, this very particular image is extensively promoted and supported by the religious beliefs as the original dwelling place where men live in the Godly realm. The word paradise literally (and originally) means ‘walled (enclosed) estate’; it insists on the idea of the wall as the ‘divider of space’ when it defines what does/does not belong to the dominant power (the owner). The wall here is not a defensive wall; the word daeza is rooted in a verb that means ‘to construct from the earth’ or ‘to be made of clay’. It divides and separates, therefore it produces space. The original description of paradise in Avesta, explicitly illustrates an image of an earthly place. This ‘enclosed estate’ occurs only once in the entire text, but that occurrence is an extremely significant one. It is where Ahura Mazda describes an earthly place: [22]

“There, on that place, shall the worshippers of Mazda erect an enclosure, and therein shall they establish him with food, therein shall they establish him with clothes, with the coarsest food and with the most worn-out clothes. That food he shall live on, those clothes he shall wear, and thus shall they let him live, until he has grown to the age of a Hana, or of a Zaurura, or of a Pairishta-khshudra.” [23]

As Patrick Healy wrote in the notes on the 52nd Venice Biennale, paradise ‘signifies and has the sense of a dwelling place, earthen enclosure, of those intimately associated with death’; [24] the place where you should eat and wear clothes, the place that you should live in: the city. The earthly image of Paradise – Terrestrial Paradise – in one of the strongest physical representation is illustrated, in the Athanasius Kircher’s Arca Noë, as a walled domain located between the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia. [25] It is formed as an enclosed square-plan; four gates, which are guarded by four angels, facing the four cardinal points. In the middle of the domain two bodies of water meet and the Tree of life is located. It is where Adam and Eve are illustrated by the Tree of knowledge positioned in the bottom-left corner of the paradise (Fig. 5). This image actually does not imply an imaginary model while it is precisely constructed out of an exceptional urban form, which is still traceable in the territory. By the vast use of this model in the Iranian plateau, paradise became a political device to divide the evil form the good, enemy from friend and the city from the rest of the territory, to re-construct the state of well-being. It developed into archetypical forms of built environment to expand the empire, peace and happiness to such an extent that ‘the earth would become part of the empire, the empire would become paradise’. [26]

This particular reading of paradise was only valid when religious ideology was used as the necessary condition for maintaining political autonomy. In Iranian history, such conditions resulted in shaping two exclusive spatio-political devices (archetype) that ultimately fostered specific urban forms: the circular city (during the Sassanid Empire, AD 224–651). In these projects the circular wall represented the Iranian ideologies, embedded in the physical form of the cities. They were not only ideological responses to the geographical constraints, but rather a ‘political project’ through which the relationship between the political theology and urban form becomes the most visible. By laying out this particular model across the Iranian territory it became a geo-political tool marking the empire at large. This very use of the wall, as a formal representation of the absolute power of the Sassanid state, developed further in the early Islamic period. A profound extension of this archetype can be seen in design and construction of the magnificent city of Baghdad, built by Caliph al-Mansur in AD 762.

The City of Peace

“It is said: When al-Mansur decided to build it he wanted to behold it with his own eyes, so he ordered that it be delineated with ashes. Then he began to enter from each gate and to walk through its passageways, its arcades, and its courtyards, which were a diagram in ashes; and he turned around and looked at the men (in succession), and at that which had been delineated of the [city]’s trenches. Having done that he ordered that cottonseeds be placed on those lines, and naphtha be poured on them; and he gazed at it as the fire was blazing up, and he comprehended it, and came to know its design; and he commanded that the foundation thereof be excavated according to the design. Then the work on it was begun.” [27]

During the first century after the rise of the Islamic Empire, it had expanded from Transoxiana to the Atlantic coast. However due to constant conflicts and wars in the mid-eighth century, which caused dissolution of the central power in Umayyad, the Islamic empire had lost its totality. After a few years of chaos, Abbasid Caliph al-Saffah, by the help of the Persians who had an inborn hatred of the Umayyads, took over the power. However it was only during the second Abbasid Caliph, al-Mansur (reign: AD 754–775), that an overall order was established throughout the empire. A new capital for this new power was indeed an imperative need. The most strategic place for al-Mansur was the Mesopotamia, close to the Persian border where he had the most support. The Caliph made many journeys in search of a site for his new capital, travelling up and down the Tigris, finally he fixed upon the site of Baghdad. In the year 761 A.D. al-Mansur decided to build its new capital city, Baghdad was still a Persian village along a canal named al-Serat on the west bank of the Tigris River. [28] The fifth of Jumada al-Awwal, 145 A.H. (August 1, AD 762) was picked by Nawbakht, the Persian court-astrologist, as an auspicious day for the city to be laid out (Fig. 6). [29]

In AD 762, when al-Mansur wished to build the city of Baghdad, he consulted his companions, and among them was Khalid ibn Barmak, [30] a Persian architect and former governor of Fars, who had converted to Islam. [31] Although no explicit evidence exists to prove that Khalid designed the plan of Baghdad according to the particular Sassanid model the circular cities, [32] documents confirm that the very spatial organisation of a monastery (Nawbahar) had been applied to the construction of the city, and in fact, the original plan of the city of Baghdad can actually be traced to a single building: a set of chambers laid out around a sacred core – most likely a Sassanid Zoroastrian or Buddhist monastery, which implied a certain way of living. The city was planned and constructed at once; unlike other early Islamic cities where the foundation of the city had been initiated by the construction of the mosque and Dar al-Imara (palace), the City of al-Mansur was built as a whole, just like a building. The Caliph named it the ‘City of Peace’ referring to the Quranic description of the heavenly paradise, the ‘City of God’ or the ‘House of Peace’, aiming to shape and house the ‘good life’.

The construction of all the buildings and quarters was started at the same time, but perhaps the most essential part of the process was the construction of the walls. The city was shaped by construction of a double wall forming a perfect circle; [33] a circular compound which was pierced by four gates opening up to the inter-cardinal points; Damascus Gate (North-West), Khorasan Gate (North-East), Basra Gate (South-East) and Kufa Gate (South-West). A ditch was stretched from gate to gate, directing the water of the canals around the city. Inside the enclosed circle a third wall separated the inner royal quarter– including the palace and the mosque– from the residential districts, at the centre of which was al-Mansur’s celestial domed palace, precisely laid at the crossroads of the world (Fig. 7). In planning of the royal quarter, the Caliph had followed Sassanid precedent, which was already prefigured in construction of the mosque and Dar al-Imara of the city of Wasit. [34] The Palace of al-Mansur (named after The Green Dome or The Golden Gate) was a square-plan of 400 cubits (207 m) a side, which was oriented towards the four gates of the city (Fig. 8). In the middle of the palace was an Iwan, a vaulted hall open at one end, while from the other end it was connected to the central audience hall at the very centre of the palace. This central hall was a square of 20 cubits in each side, covered by a dome. Above this hall was a second room of the same size also covered by a dome. The famous Green Dome was the latter one, which from outside reached the height of 80 cubits (41 m), as it was the highest edifice in the city. From the opposite side of the Iwan, the palace was connected to the Great Mosque, in which they shared the wall of qibla. The Mosque did not exactly face the Mecca point, as it should have done, the cause being that its plan having only been laid down after the palace was completed, the quadrangle of the mosque, for the sake of symmetry, had to conform to the already existing lines of the palace walls. [35] This mosque stood for half a century, when it was pulled down by Harun al-Rashid (AD 808-9) who replaced its primitive structure by a structure solidly built of kiln-burnt set in mortar. However the construction of the city was interrupted two times, but most of the buildings had been completed in AD 763 when al-Mansur ordered to relocate the Treasury and Diwans (Public offices and Institutions) from Kufa to the new capital. In AD 766 construction of all the buildings including the houses, public buildings and the royal quarter was finished.

The area between the second wall and the third (inner wall) was divided by four vaulted galleries, which ran from the main gates to the gates of the inner zone, thus the in-between zone was arranged into four quadrants. Unlike the outer ring (which was vacant), these quadrants were occupied as the residential ring. They were built over by the houses of the immediate followers of the Caliph al-Mansur, to whom had been granted here plots of land, and before long the whole space had come to be covered by a network of roads and lanes. [36] Two encircling streets of 25 cubits wide separated the residential quarters from the outer and the inner walls (Fig. 9). The grid of the street were planned in such a way that the houses in the streets and lanes of each quadrant could also, at need, be closed off by these roads by strong gates. [37] Each quadrant was sub-divided into city blocks, which were separated by radial streets. Al-Yaqubi mentioned these streets that were named after the group who were settled there or, in some cases, after clients who had been charged with the building of them. [38] Close to the Basra Gate a police headquarter, [39] prison, [40] and guardhouse were placed. On both sides of the main galleries there were series of arcades connecting the four gates to the inner zone, these spaces, until AD 773 were the market place (bazaar). However before many years had passed the Caliph ordered all the shops to be removed from within the city and he then built the suburb of Karkh for the accommodation of the market people and the merchants, the arcades thus cleared of the shops being used as permanent barracks for the city police and the horse-guard. [41]

The organisation of the residential area was in fact the most emblematic spatial configuration of the city; the residential units were designed as a ring around the central void; they were both excluding and at the same time binding the city together. In the City of Peace, it was not only the earthen walls that excluded the outside from inside, but rather it was the inhabitants that were set around the centre to mark the city; the form of life itself became the form of the city. It was this inhabitable wall that related the individual and groups to each other and to the sovereign. And the city was a spatial apparatus, housing this relations; it embodied the ideological diagram of power within its parts and exposed it through its urban form.

It was only AD 814 that the City of Peace turned into ashes; [42] in its very short life, the city manifested thoroughly an ideal form, and remained abstracted just like the way it had been delineated; a diagram in ashes. It exposed the relations between forces, which constitute the power. The City of al-Mansur then, was both specific, in that it precisely maps the space of individual confinement, and universal, in that it (imprecisely) refers to an entire social regime. It manifested a spatial condition that embodied a political idea; a diagram of the ideological power, not only between the sovereign and the political subjects but also, among the people itself. This tension was carefully expressed through the architecture of the city, where this life proliferated entirely. In fact the city housed and, at the same time, shaped specific form of life through its mechanism. The City of Peace held such a tension, which was charged with the task of not simply framing the people, but enabling them as the political subjects by making the possibility of action and reaction, movement and resistance. Through its emblematic plan it was able to incorporate both spatial and political forms. However there was a sense that the ideal, embodied in its form, which haunt the real but perhaps it had never been realized as such. [43]

The City of Peace nevertheless manifested a political project: the wall of paradise has been developed in the Islamic conception of city (medina) while it becomes not merely a wall but an inhabitable space that contains faithful bodies; it appears in the form of a camp where faith arrives as the decisive factor to mark the community of the faithful (Fig. 10). The faithful bodies therefore, are granted a great privilege to enter this place: the city. In fact, the eternal paradisiacal house of mankind, which had been abandoned due to the original sin, is reconstructed in the form of the terrestrial paradise or medina. Topologically the concept of the camp, like the wall of paradise, is borrowed to define the space in the form of a bounded container, which is not reducible to any other structure. The camp, in its generic, but at the same time exclusive structure, can house specific groups of people. It is not a sacred place in itself but since the space is constituted by the occupants’ (faithful) bodies, it is, therefore, constantly ideological and spatial. This ideology is exclusively represented in the act of foundation of the early Islamic cities; it appeared in a concrete spatial configuration while the Persian ideological city model met the Islamic state’s will to assume the shape of an empire.

Through the project of the City of Peace, al-Mansur unified the political and religious authorities and he reclaimed the total sovereignty of the state. The space binds and, at the same time, defines the life of the subjects in relation to the power. It marks the territory of the power, by making borders and walls, outside which the life is not protected and defined. In fact this is the relation that characterises the city as a political project, where political power (state) constantly produces such a condition to confront life to death. This inherent tension physically realises in the form of inhabitable structure whose nonfigurative monumentality represents the utmost order and performs as a life-sustaining machine, protecting the lives of the political subjects. In this ideological model, the wall not only accommodates the tension, but shapes specific urban form constituted by the lives of its subjects.

Such a project is a result of a specific form of power, which is defined as sovereign; who can decide on the moment of urgency and has power over the life of the subjects. [44] This particular concept of city has become more explicit when an absolute power in the form of a sovereign state assumes a visible and operative dimension. The heart of the city, in this definition, is the state– a mortal god, whose task is to provide people safety and security. In a Hobbesian image, the sovereign can be illustrated as a monster, made up of the bodies of its political subjects (citizens) and aggressive when confronted. He comes to be in the first and becomes the cause of the existence of the city and its parts instance, ‘and the cause of the presence of the voluntary habits of its parts and of their arrangement in the ranks proper to them’. [45] By holding all juridical, political and social legitimacies, the sovereign ruler closely resembles the image of God to essentially transform the concept of ideal city into an ‘earthly paradise’.

Spaces of sovereignty

Seven centuries before Hobbes, al-Farabi, described the “excellent city” as a city through which its inhabitants aim at co-operating for the things by which felicity and happiness (al-Sa’ada), in its real and true sense, can be attained. He further highlights that this condition is only possible when a ruler, whose decision is analogous to God’s acts, [46] holds the people together by constructing the ideal city. For Plato and Aristotle the concept of the ideal city, goes beyond the mere actuality of the Greek polis and the very paradigmatic case of Athens, it becomes apolitical concept; an ideal kingdom of reason, where the only person eligible for ruling the city is philosopher-king. However in the Zoroastrian and Islamic thoughts, this concept appears essentially as an existential one; the ideal city is a terrestrial paradise where the ruler ‘is a person over whom nobody has any sovereignty whatsoever’. [47] The Sassanid King or the Islamic Caliph, through the act of separation, frames the lives of the people and directs them toward the happiness. Therefore, the possibility of having a good way of living is conditioned by presence of a sovereign power without which no political life can be achieved. The city is in fact the place that this power relation has to be manifested. In this definition the sovereign’s power does not appear anymore as a killer monster whose power is constituted in the right of ‘taking or giving life’, but it provides the security and safety through the ‘administration of life’; he protects and at the same time defines form of life, as an act, analogous to the way the sacred power performs. Historically this condition is reflected in a way that the urban civilization emerged and developed in the Iranian plateau.

The wall (paradise) becomes inhabitable and forms the city; through its spatial configuration it bears the very meaning of separation and therefore of the spatial order. The interior is managed, organised and ruled by the (divine) sovereign power, while the exterior is an unknown, unmanaged, and therefore uncivilised domain. The wall not only protects life and fosters it within the harsh landscape, but even assumes symbolic dimensions when it goes to other cultures, religions and different geographical conditions; within the context of Christian symbolism, the wall signifies divine intervention, redemptive interruption of the natural order, ‘pointing up the power of Grace to undo the natural propensities of human will [and signifying] life-giving separation between nature and Grace’. [48] The interpretation can be compared to the concept of terminus in the Roman Empire. It appears as an active producer of space that simultaneously performs processes of territorial definition and spatial partition. As Matteucci describes it: ‘On the one hand, in marking the end (or the finis) of a territory, it functions as a means of delimitation of the land. On the other hand, in dividing two or more pieces of territory, it also performs a process of separation’. [49] Like termini, paradise and medina separate the urbs from the pomerium, the sacred and the profane spaces, the city from the country, and the territories of the empire from the rest of the world.

The wall in the Sassanid cities and the City of Peace fundamentally implies the idea of pairi-daeza. It turns into a geopolitical device, while it outlines the order on the land. In these cases the executive power decides and divides, however in modern times it is the legislative power that shapes the border. ‘The sovereign becomes the living nomos’; [50] he constantly (re)defines friends and enemies and hence modifies the walls. The city therefore is adjusted to every new condition. As the bio-political bodies are the subjects of the modern state, this process of constant division and redefinition of space (wall) appears in every units of the city: dwelling space, and the state of exception becomes the norm. [51]

More than narrating historical phenomena this reading offers a way (lens) though which the contemporary form of the city can be read, where the power relation does not appear anymore as encircling walls around the cities but rather it is conducted through the most common architecture of the city; the domestic space. While previously environmental constraints and geopolitical strategies were the main drivers behind the use of religion as the ideology of the state, in modern times it is the ideological thesis itself, which has been used to theorise the ideal and hence the legitimate form of power. The wall as an apparatus once again becomes instrumental in re-establishing the relationship between the state, the people and the territory. It is no longer presented in the vestige of a historical political-geographic model that appropriates life of the individuals for the sake of “living” itself. [52] But it is rather a geo-biopolitical tool that shapes certain form of life: a life that cannot be separated from its form. In a way ‘space becomes ‘vital’ – and life becomes spatialised’. [53] The house therefore, as the smallest constituting part of the city (inhabitable chamber), holds the tension.

In this perspective life is defined and shaped in relation to power, while power ‘founds itself on the separation of a sphere of naked life from the context of the form of life’. [54] It is not just the rule that implied a particular life but the way of life also forms the rule. [55] The city then, like a monastery, not only territorialises this relation, but it is the only condition, through which certain form of life can be achieved. Through these inhabitable walls, bound the individual and groups to each other and to the sovereign. By housing these relationships the city embodied the ideological diagram of power within its parts and exposed it through its urban form (Fig. 11). Here indeed paradoxically the vertical application of power of the sovereign ruler is reversed, while the rule becomes the way of life (habitus) and life defines the rule in a dialectical relation, and it is spatially manifested through the very tectonic of the city.

Bibliography

- Agamben, G. 1998. Homo sacer: sovereign power and bare life. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 86 p.

- Aga mben, G. 2000. Means without end: notes on politic s. Minneapolis-London: University of Minnesota Press, 4–5.

- Agamben, G. 20 05. State of e xception. Chicago: Chicago University Press. 70 p.

- Agamben, G. 2013. The highest poverty: monastic rules and form-of-life. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 13–16.

- al-Farabi, M. 1985. The perfect state or Mabadiara ahl al-madina al-fadila. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- al-Tabari, M. 2007. Annales or Tarikh al-Tabari, vol. 9. Damscus-Beirut: Daribn Katheer. 932 p.

- al-Yaqubi, A. 1861. Kitab ol-boldan or Book of the countries. Leiden: Brill, 11–13.

- Beckwith, C. I. 1984. The plan of the city of peace, Acta Orientalia Hungarica 38(1984): 143–164.

- Bremmer, J. N. 1999. Paradise: from Persia, via Greece, into the Septuagint, in G. P. Luttikhuizen (Ed.). Paradise interpreted: representations of biblical paradise in Judaism and Christianity. Leiden: Brill.

- Cavalletti, A. 2005. La Città Biopolitica. Milan: Mondadori. 206 p.

- Creswell, K. A. C. 1940. Early Muslim architecture, part II. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Creswell, K. A. C. 1979. Early Muslim architecture, vol. I, part I. New York: Hacker Art Books.

- Driscoll, J. F. 1912. Terrestrial paradise, in The Catholic encyclopedia, vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 519 p.

- Gorham, G. M. 1856. The Cyropaedia of Xenophon. London: Whittaker.

- Hanaway W. L. Jr. 1976. Paradise on Earth: the terrestrial paradise in Persian literature, in E. B. Macdougall, R. Ettinghausen (Eds.). The Islamic garden. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University. 63 p.

- Harper, W. R.; Wallace, J. 1893. Xenophon’s Anabasis, seven books. New York: American Book Company. 92 p.

- Healy, P. 2007. La Difesa della Natura, notes for the exhibition organised by F.I.U Amsterdam in 52nd Venice Biennale.

- Kheirabadi, M. 2000. Iranian cities: formation and development. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. 93 p.

- Khosravi, H. 2012. Medina [online], [cited 14 November 2013]. Available from Internet: www.thecityasaproject.org/2012/06/medina/.

- Kircher, A. 1675. Arca Noë. Amsterdam: J. Janssoniuma Waesberge. 230 p.

- Le Strange, G. 1900. Baghdad during the Abbasid caliphate. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 33–34.

- Lincoln, B. 2003. À la recherche du paradis perdu, History of Religions 43(2003): 139–154.

- Lincoln, B. 2007. Religion, empire and torture: the case of Archaemenian Persia with a postscript on Abu Ghraib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 57 p.

- Matteucci, P. 2006. Sovereignty, border, exception, in P. Bonifazio, E. Bellina (Eds.). State of exception. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press. 14 p.

- Morris, C. D. 1880. Xenophon’s Oeconomicus, The American Journal of Philology 1(2): 169–186.

- Pinder-Wilson, R. 1976. The Persian garden: Bagh and chahar bagh, in E. B. Macdougall, R. Ettinghausen (Eds.). The Islamic garden. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, 70–85.

- Prickard, A. O. 1907. The Persae of Aeschylus. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Schmitt, C. 2005. Political theology: four chapters on the concept of sovereignty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 5 p.

- Smith, H. H. 1971. Area handbook for Iran. Washington, DC: American University.

- Stewart, S. 1966. The enclosed garden. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. 59 p.

- Stronach, D. 1990. The garden as a political statement: some case studies from the Near East in the First Millenium B. C., Bulletin of the Asia Institute (4): 171–80.

- Stronach, D. 1989. The royal garden at Pasargadae: evolution and legacy, in L. De Meyer, E. Haerinck, (Eds.). Archaeologica iranica et orientalis: miscellanea in honorem Louis Vanden Berghe. Ghent: Peeters Presse 476–502.

- Wendell, C. 1971. Baghdad: imago mundi, International Journal of Middle East Studies 2(1971): 99–128.